Limmer lists GOP police reform offers

Several agreements reached; Mariani expresses frustration with Senate priorities

Minnesota Senate Republicans have put six police reform offers on the table in special session negotiations, Session/Law has learned. Some are agreed to. Others are not.

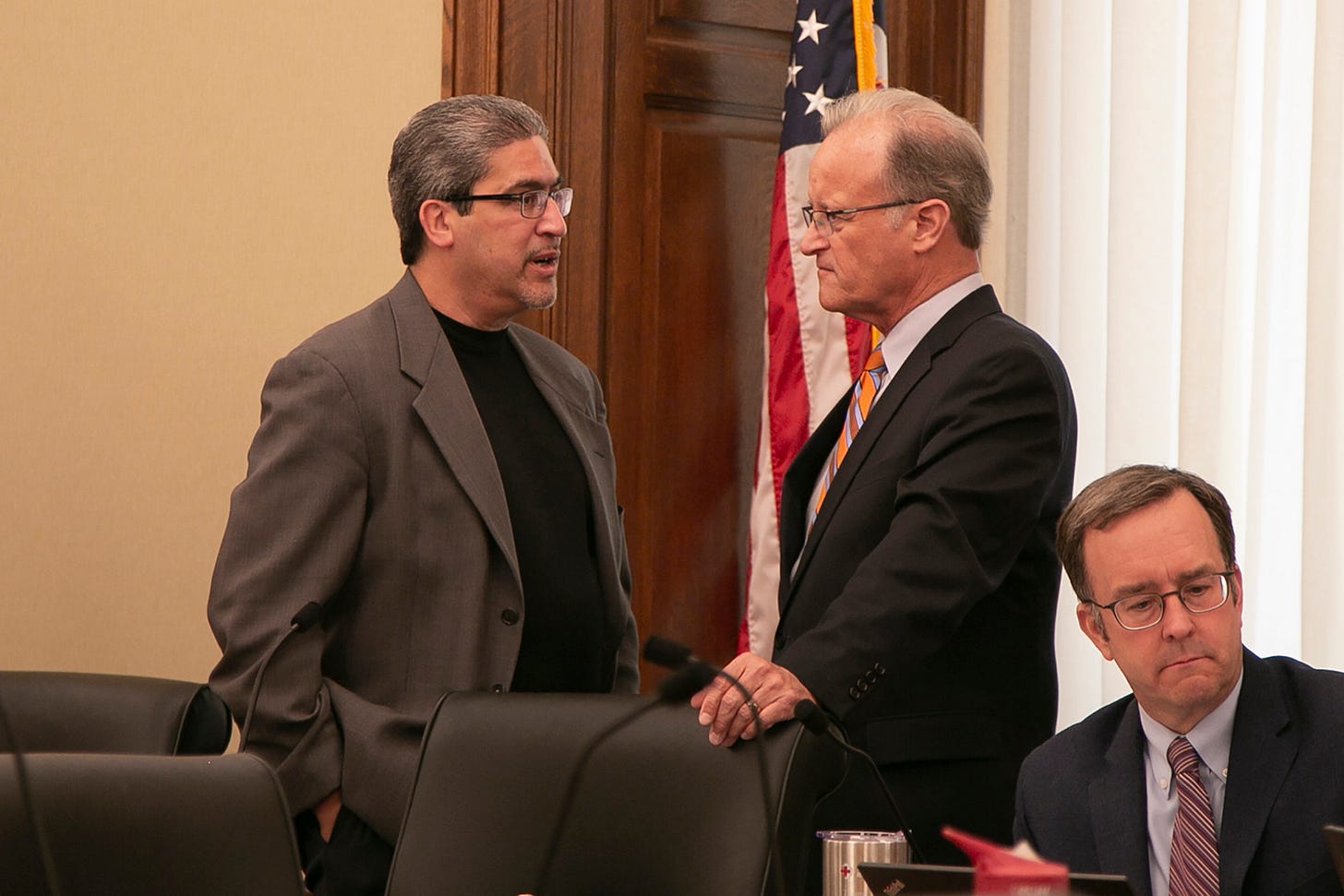

Sen. Warren Limmer, R-Maple Grove, spoke with us late Wednesday, just hours before House Speaker Melissa Hortman told WCCO Radio that legislative leadership had stepped into the stalled public safety bill negotiations to help settle matters.

House Public Safety Chair Carlos Mariani, DFL-St. Paul, answered questions about his reaction to those offers via text early Thursday morning.

In a brief text exchange at 12:30 p.m. Friday, Limmer said “nothing new” of note has happened since those conversations.

Here is what we know.

On the table

While there is partisan disagreement about whether one policy deserves to be classified as “police reform,” GOP senators say they have put six such offers in play during the special session.

Five were described to us by Limmer late Wednesday. The sixth was identified by Senate Majority Leader Paul Gazelka, R-East Gull Lake, earlier this week.

Here are the ones Limmer said he has offered.

Extremist cops

The House omnibus from the regular session included a model policy that bars officers from associating with white supremacist groups. Republicans balked, saying it shaded toward curtailing cops’ First Amendment rights of association.

“We rewrote that,” Limmer said. “We would prohibit the association of officers with ‘violent extremist groups,’ as defined in a list created by the FBI.” Limmer said Wednesday he wasn’t sure, but thought Democrats might’ve agreed to that offer.

He might have to think again.

“The issue is precisely white supremacy,” Mariani said. “Changing the bill to avoid it is not ‘accepting’ anything.”

The Peace Officer Standards and Training Board, Mariani noted, has already voted without legislative prompting to develop a model policy specifically banning white supremacists. “We are not going supersede them with this statutory law to avoid naming it,” he said.

Public assemblies

Since early in the 2021 regular session, before the SAFE Act mutual-aid finance bill died on the House floor, Democrats have been pushing hard for yet another POST Board model policy, this one protecting the First Amendment rights of protesters. It was in their regular session omnibus, too.

Limmer said the Senate has swung around to accepting that idea. “We approved a model policy language for public assemblies,” he said.

Mariani confirmed this is an area of agreement, though he’s not especially enthusiastic about it. He said Republicans have watered it down a bit and noted that, like the previous item, the POST Board already is developing a policy independently. So a new statute isn’t really needed, Mariani said.

“Still, in order to give and take, we can accept it,” Mariani said. “But it is not our offer. We are accepting theirs.”

Travis’ Law

This measure requires 911 dispatchers to refer mental-health crisis teams to emergency calls when appropriate, not only police. It’s named for Travis Jordan, 36, who was killed by police in 2018 after his girlfriend notified authorities that he threatened suicide. Allegedly, Jordan confronted responding officers with a knife and was shot.

The provision was included in a DFL offer to the joint House-Senate public safety conference committee in early May. Limmer’s counter-offer alters it a bit, he said.

“Their proposal wanted it in every county, but probably not every county has that kind of a resource. That’s why we added ‘where available,’” he said. “I’m not sure if they accepted that or not.”

They haven’t. “No agreement,” Mariani said. “They want to water down what advocates and the family whose son was killed by police have asked for.”

Matthew’s Law

This is a Republican measure; its companion bills were authored by Sen. Dave Senjem, R-Rochester, and Rep. Duane Quam, R-Byron. It’s named for a drug-addicted confidential informant who lost his sobriety while making controlled buys for Rochester police. He died of an overdose.

Among its provisions, Limmer said, the bill would require that warnings be given to police informants about the hazards or temptations they might face while working with law enforcement. It passed 66-0 in the Senate and made it to second reading on the House floor, but no farther.

House DFLers included it in its early May offer, however, so it is on the table. Still, Mariani complained that it strictly reflects the Senate’s pro-law-enforcement stance. “We offered it as part of our approach to equity: that we do equal policy/funding to hold [police] accountable while supporting law enforcement,” he said.

The upper branch has not really reciprocated, Mariani said. “The Senate only wants to do one side of that and ignore communities.”

The Hardel Sherrell Act

This measure is named after a county jail inmate who died in his own filth, stricken and paralyzed, reportedly because jail staff thought he was faking a medical condition. The policy would strengthen standards by, for instance, requiring that relevant inmate health data be shared with medical professionals.

The Senate position now favors its inclusion, Limmer said.

Mariani called it “a good bill,” but said it is misplaced on a list of police reforms. “Not a police accountability bill,” Mariani said. “It’s a corrections reform bill.”

Two more

Mariani said that another measure, not mentioned by Limmer, also has sign-off by both sides. It would allow the collection of some police data currently classified as private.

Also missing from Limmer’s list of offers and agreements is the conservation officer body-cam provision that Gazelka mentioned to reporters earlier this week.

‘Four or five’

Gazelka told reporters Monday he believed there were “four or five” areas of agreement between the House and Senate on police accountability. One of them, he said, was the deal to equip conservation officers with body cams. He didn’t name the others.

While Mariani has acknowledged the body-cam provision is fine legislation, he again expressed frustration that it reflects the Senate’s insistent tilt toward law enforcement—not the community. “It’s a department ask,” Mariani said. “Again, one side only of equity.”

By Mariani’s count, there is agreement on just three “small issues” related to police reform—and even those were accepted by House DFLers “with contingencies,” he said.

“That’s just three small issues—and ones that don’t address the practices that led to the killings of Daunte [Wright], George [Floyd] and Philando [Castile],” Mariani said. “That demonstrates how unprepared and unwilling the Senate is to address a major life-and-death issue of these times.”

It’s not clear why Limmer didn’t mention the body-cam measure as a GOP offer. It could indicate the proposal more strongly reflects leadership’s priorities than the negotiating conferees’. Gazelka acknowledged early this week that legislative leadership’s “fingerprints” were already on a number of special session bills.

Progress

Taking a quick step back, it’s important to note that many provisions of the public safety/judiciary budget bill are agreed to.

The bill, which has a $105 million, two-year new-spending target, covers much more than police reform. It also funds the courts, departments of Corrections and Public Safety and public defenders, among many other related budget areas. Limmer said a great many of those are now resolved.

Further, Hortman on Monday described a substantial breakthrough on the omnibus—though it doesn’t directly relate to police reform. That’s a deal to keep the spending target at $105 million while deleting a Senate demand that a $30 million recharge to the depleted Disaster Assistance Contingency Account be taken out of the public safety/judiciary budget.

Hortman said that concession could finance violence-prevention measures that are high priority for Democrats and perhaps pave a wider path toward bipartisan accord on the overall bill.

That could be, but there is little evidence, at least for now, that things are working out that way. And the wide gap in the two chambers’ attitudes toward police accountability is the chief reason why.

In Limmer’s view, many of the 100-plus, DFL-championed police policies would only work to sap law enforcement’s strength at time when an ongoing Twin Cities violent-crime wave suggests that more, not less policing is what’s needed.

“I find it very uncomfortable to weaken the authority of police officers while the Twin Cities are experiencing a huge epidemic of violent crime,” Limmer said. “It does not encourage me to pass a lot of police reform at this time.”